How to think about durable execution

An in-depth look at durable execution, and how it relates to task queues, message brokers, and other orchestrators.

Back when I was CTO at Porter, we were responsible for managing deployments of hundreds of Kubernetes clusters into customer AWS accounts. In the early days, this was all built using a single-replica deployment called porter-provisioner , which was essentially a Go binary automating a bunch of Terraform and Helm commands. This was circa 2020, and one of our users asked if we had considered Temporal for this workload. The next day I opened up the Temporal docs, read for about 30 minutes, and came away with: nothing. For some reason, I couldn't wrap my head around how durable execution worked, or why it was relevant to our workload.

I'll avoid talking to vendors at all costs, so I decided to table my research for the time being and kept plugging away at building our own in-house orchestration system. Over the next few years of working on this system - writing a second and third version of the provisioner - I kept returning to Temporal, because I sensed that it should be the right fit for my workload. But I still didn't get it. I understood the benefits that they were selling, but I'm a bottom-up thinker; I need to understand how something works under the hood before I can use it.

After I left Porter, I spent a while researching durable execution platforms, starting out by building my own open-source Terraform automation project using Temporal (since abandoned), introduced Temporal as the CTO of a different company, and eventually started Hatchet.

Here's the post that I wish I read at the time: an in-depth look at durable execution, and how it relates to task queues, message brokers, and other orchestrators.

The task queue

We're going to start by introducing the traditional task queue. While most apps start with a REST API, there comes a time when work is either too long-running or resource intensive to run inside of an API handler. At Porter, this was needed on Day 1, when we needed to provision infrastructure for customers; since AWS can take over 30 minutes (!!) to provision a new EKS cluster or database, keeping a handler alive for that amount of time wasn't an option.

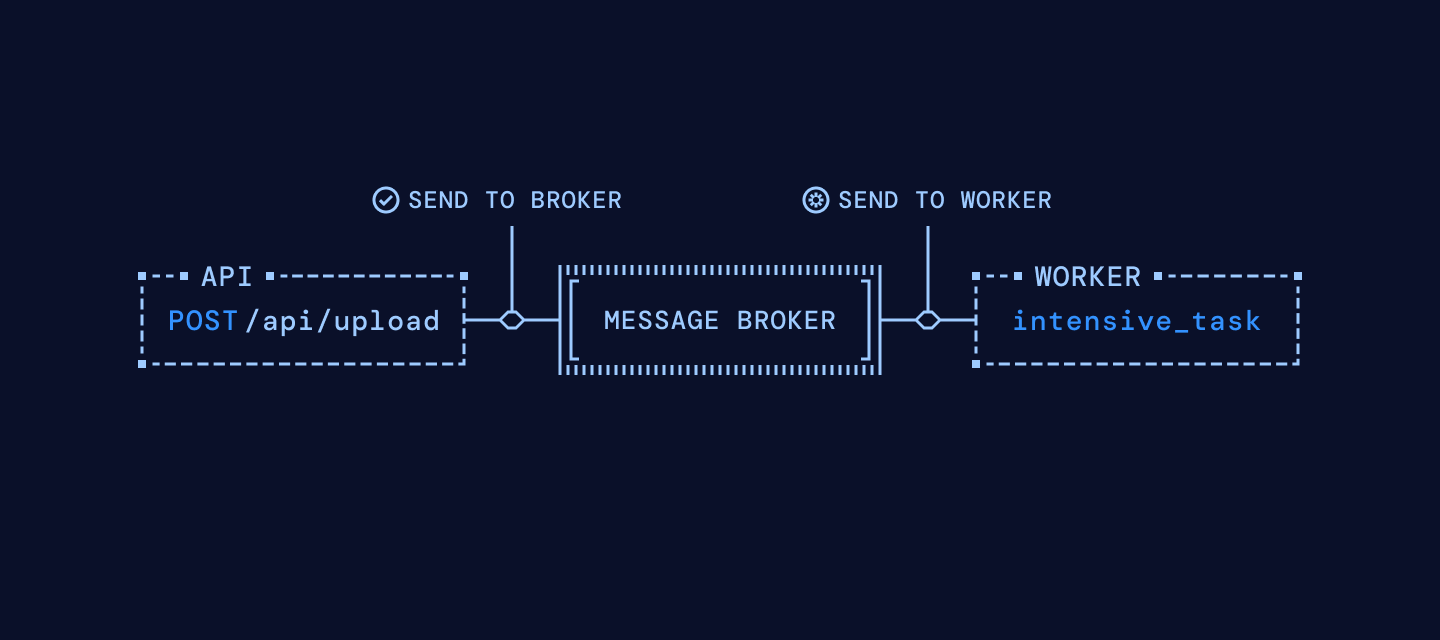

At this point, you typically introduce the task queue: a system which ensures that background tasks get scheduled and run on a separate set of workers. Task queues have varying properties: Durability at the messaging layer (for retries), durability at the task layer (for replays), exactly-once processing, the list goes on. Your architecture may look like this:

The message broker

It would be ill-advised to pass messages directly from your application to your workers without an intermediate persistence layer, or else you risk losing messages when your workers crash. So while a task queue could in theory be implemented using only a protocol like REST or gRPC (and yes, the Porter MVP invoked tasks using this mechanism), a task queue typically utilizes a message broker, which can also have varying properties: Durability, message retries, dead-letter queues, etc.

Redis, RabbitMQ, and database-as-queue are popular options for the persistence layer.

Simple tasks

Before proceeding, I'd like to introduce the term idempotency: in this context, it means that if you invoke the same task twice, it has the same effect as calling it once.

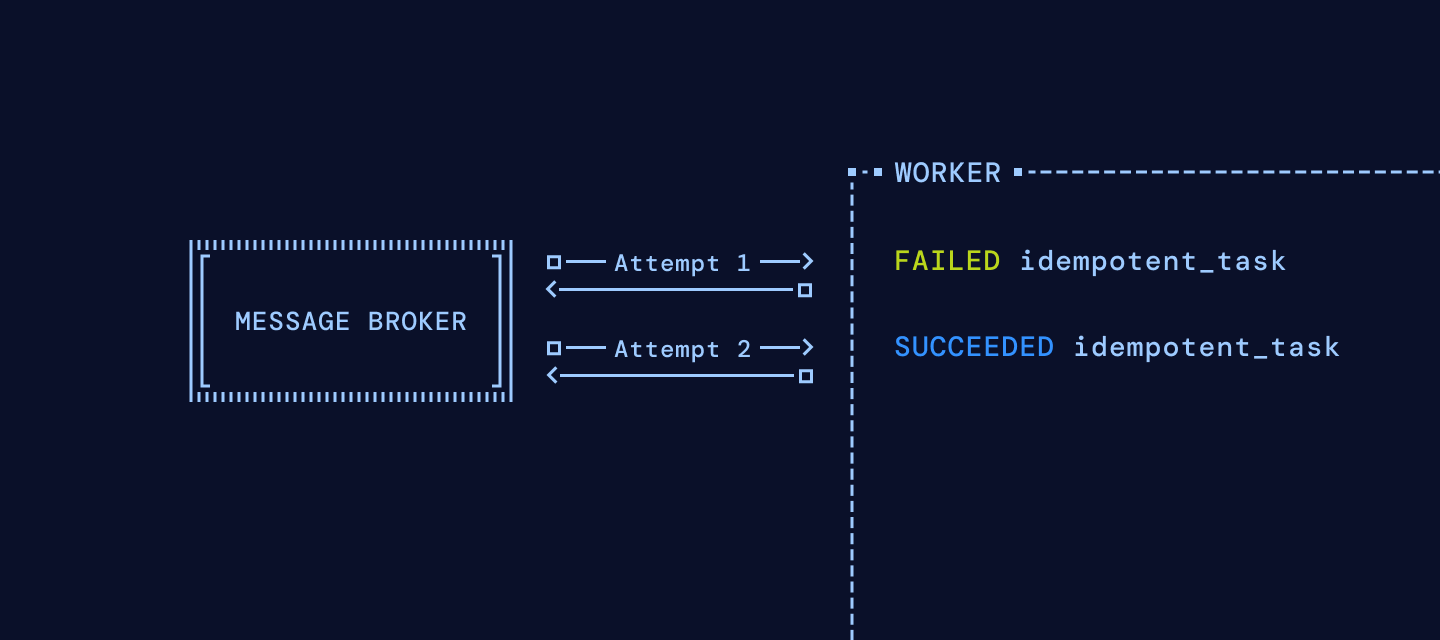

Ok, so we have a simple task queue in place; we enqueue tasks from our API, and we process them on our workers. And this next part is crucial: if your task is easily idempotent, and can update application state via a single database transaction, then this is likely all you need.

By easily idempotent, I simply mean either the task is stateless (inherently idempotent) or you can make the task idempotent with a minimal change.

For example, if you are processing a file upload, and your task consists of 2 steps:

- Call out to an external API to process the file upload, and

- If the file is not already marked as processed in your database, update its status to

PROCESSED

…then you have very few failure modes. If your worker crashes while processing your task, and you have configured your message broker to resend the task to a new worker on failure or visibility timeout, you will end up with consistent application state.

Complex tasks

But what happens when tasks aren't so simple? Consider a model of our workload at Porter:

- Create a new database entry to represent the infrastructure deployment

- Call the AWS API to start provisioning a new AWS resource

- Poll the AWS API for results

- Update the database entry which represents the infrastructure deployment

- (repeat 2-4 for 100s of AWS resources, over at most ~1 hour)

This task is not easily idempotent; it involves writing a ton of intermediate state and queries to determine that a step should not be repeated, which gets more difficult because the execution graph can change in between runs (it's also not possible to ensure that the two sources of state — the AWS resources and the deployment status — will ever be fully consistent, but that's a different story).

There are other reasons for not being able to model your workload as a single idempotent task running on a single worker, such as:

- One part of your task is very resource-intensive, and needs to run on a different machine from the other parts of your task. You'd like to split the task into smaller, more manageable subtasks.

- Your task needs to write data to an external source, and cannot do so in a way that's easily idempotent. Typically this is seen when the task has side effects which are stateful. A modern example of this would be a mutating KV cache for an agent's context.

- Perhaps you have 50 different microservices, each one responsible for a different part of the system. Your task might need to call different microservices, all using potentially separate databases or underlying state stores.

This is typically where you start to explore an orchestration engine or a workflow engine, to bring some order and visibility into what is becoming a very chaotic, distributed system, and in particular to reduce the number of failure modes that can occur in this system.

And we finally get to the motivation of durable execution: it is just one approach to orchestrating and managing the state of a set of interrelated tasks (frequently called a workflow). There are many others: Systems which implement DAGs, Celery's chains and chords, event-sourcing, homegrown state machines, each targeting slightly different problems.

The specific solution provided by durable execution platforms is to persist the intermediate state of the workflow in a separate data store, and enable the workflow to start from this “checkpointed” state on subsequent runs.

Durable execution

There are a few ways you could persist this intermediate state. The solution utilized by what I call external durable execution state stores — like Temporal and Hatchet — is to persist each workflow's incremental state in an external system, and provide the workflow with the ability to skip any subtasks (or more generally, any actions persisted to the durable event log) which have been previously called by replaying the durable event log on a retry.

Let's see how this would work for a simple, two-step function which crashes halfway through. The function could look something like this:

On the first execution, let's imagine that the machine the workflow is running on hits an OOM - this will forcefully terminate the process, so there's no possibility of recovery. In this scenario, this OOM occurs after we have run the chargePayment step, but before we have run sendConfirmationEmail.

On the second execution, the workflow can automatically skip the first step, and move directly to the second step, as the execution history shows that chargePayment has already run.

To be a bit more precise, durable execution basically contains three useful properties:

- Workflows are retried until they run to completion. This way, if a machine crashes, the workflow can be resumed on a new machine.

- Each subtask (sometimes called Activities) invoked from the workflow is dispatched exactly once using an idempotency key, even if the workflow is retried multiple times (though the subtask itself may be retried if it fails).

- The workflow must be deterministic. Each workflow tracks an append-only event log to ensure that the ordering of subtask invocations is invariant (or more generally, the ordering of all operations in the workflow, durable events and durable sleep included, is invariant). As a result, the idempotency key is typically a unique id for that workflow instance along with the index of the subtask, though idempotency and ordering can be tracked separately.

The only requirement: determinism

That last property, that workflows must be deterministic, is the one major drawback when it comes to writing a workflow in a completely durable manner. This means that the order of subtasks (or more generally, any action taken in the workflow) cannot change between retries of the workflow. This typically bites developers in a few ways:

-

Iterating over an object or array whose elements might change between executions. For example, iterating over a Go

map[string]any, which randomizes iteration order, will result in non-determinism. -

Making a network or database call which may fail or return a different result when it is run a second time. As a result, durable workflows require that there are no side effects in the workflow function itself other than calls to the durable execution engine, with side effects pushed into the individual tasks the workflow calls.

-

Pushing a code change which rewrites part of the execution history. For example, if I pushed a code change for the method above to switch the order of steps 1 and 2, this would be a violation of determinism:

Loading syntax highlighting...

This is quite a restriction: all database calls, external API calls (other than those to the durable execution engine), or local calls to disk must be performed inside of the subtasks themselves.

Solved problems

While this is a very simple model for program state, it solves a number of otherwise difficult problems.

Problem 1: guarding against unexpected failures

Applications usually fail in expected ways: your database write violates a foreign key constraint, querying an API results in a non-200 status code, etc. These application failures are easy to reason about and to model out, typically involving some kind of try/catch, retry strategy or require a code change to resolve.

But the more difficult failure mode to resolve is unexpected, transient infrastructure-level failures. This could be an OOM, a machine failure, network issues, etc - things that are difficult or impossible to guard at the application level, because they usually prevent you from resuming your program!

Durable execution helps guard against these failures by allowing you to resume from the last checkpointed program state. Given that the workflow itself is only composed of actions which have a corresponding entry in the durable event log (because of the determinism constraint above), this makes the workflow state fully durable.

This does not mean that durable workflows can persist the program state of the subtask (unless the subtask is also a durable workflow). If the subtask crashes halfway through, it can be retried, or it can throw an error to the durable workflow and the durable workflow should handle it. Any fatal errors thrown by the subtask are also persisted to the durable event log, so on subsequent retries of the workflow, the subtask will continue to throw the same error.

Problem 2: implementing complex workflows

One major benefit of durable execution is that you can procedurally define your workflow, as opposed to defining your workflow declaratively (i.e. step 1 -> step 2 -> step 3). So although execution history cannot change between retries of the same run, being able to write workflows as procedural code allows you to choose a different execution path between different runs of the same workflow.

This is also why durable execution solutions tend to be a popular choice for implementing automation or workflow features into a SaaS app - for example, an app that helps build user activation journeys and sequences. In these cases, registering a set of pre-defined workflows with the orchestrator is difficult to scale, because there can be hundreds of thousands of user-defined automations.

Problem 3: avoiding unnecessary long-running or resource-intensive work

Even if there's not a need to reduce unexpected failures or implement more complex workflows, a last potential benefit of using durable execution is to skip intensive operations and tasks if things need to get retried. For example, if step1 is to process a very large file and upload it to S3, you can think of the durable event log as a built-in cache; on a retry, you don't need to repeat processing.

It is not a silver bullet

That said, it's worth tempering expectations about what durable execution can and can't do. I've seen two misconceptions when it comes to durable execution:

- It's the key to our system being more reliable - while it's likely to be a key component in your reliability story, there might be some higher-leveraged fixes you can make. If you're dealing with transient failures, the simplest solution is: reduce the number of transient failures. Rewriting your complex business logic to use durable workflows is a big lift. And while durable execution helps you recover program state, it doesn't help you if your application state is buggy. These are not the same thing!

- We should replace our queueing system with durable workflows - if you're evaluating durable execution platforms, there's a possibility that you should replace part of your queueing system with durable workflows, but many stacks typically have great use-cases for traditional task queues, or even DAG-like systems, which don't involve the overhead of a durable execution platform. Remember, persisting intermediate program state comes with overhead, both in terms of developer experience, but also in terms of $$$.

It took me a while to figure out exactly where and how durable execution makes sense, and where it makes sense to use a more traditional queue instead. I hope this helps make the difference more clear; and if you think your workload might benefit from durable execution or improved queueing, please give Hatchet a spin!

Subscribe for more technical deep dives

Stay updated with our latest work on distributed systems, workflow engines, and developer tools.